This week, researchers at Hiroshima University showed off a new terahertz transmitter that is just as powerful as its predecessors, but should ultimately prove more affordable for commercial applications. In a demo at the International Solid-State Circuits Conference in San Francisco, they presented a device capable of delivering data at breathtaking speeds of more than 100 gigabits per second at a frequency of 300 gigahertz.

At its very best, the transmitter can shuttle data at 105 Gb/s, which is 2,100 times faster than the peak cellular speeds of 50 megabits per second available through LTE. After a successful demo, the transmitter could find its way into future wireless applications that require low latency and high bandwidth.

Though other transmitters have achieved speedy data rates in the terahertz range before, the group says theirs is the first to also be based on a CMOS integrated circuit, which means it’s potentially more viable for commercial base stations or devices.

“This is quite a step for this kind of technology, because it relies on something that is freely available and could be easily implemented, compared to all of the other techniques,” says Riccardo DegI’Innocenti, a researcher at the University of Cambridge who was not involved in the work.

Terahertz waves are shorter in length and are broadcast at much higher frequencies than the microwaves used today for smartphones, household devices, or military radar. For example, Wi-Fi devices emit waves that measure about 12 centimeters in length at a frequency of 2.4 GHz. Waves in the terahertz range span less than 1 millimeter and start at 100 GHz.

Other teams have demonstrated competing terahertz transmitters that deliver data at speeds even faster than those shown by the Hiroshima group. However, these systems often relied on technology that was bulky or which could not easily scale.

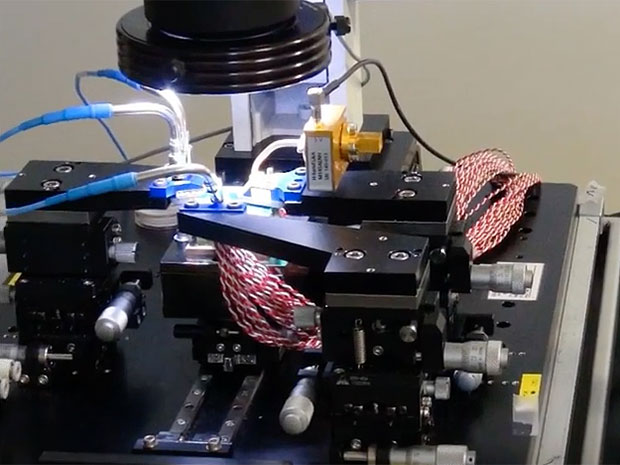

In contrast, the new transmitter has a 2-by-3-mm footprint, and was created using a 40-nanometer CMOS process. “There are many ways also to build a terahertz wireless system,” says DegI’Innocenti. “However, this is still progress because the CMOS technology was sort of lagging behind.”

Minoru Fujishima, a professor at Hiroshima University and a member of the team that developed the transmitter, says the primary advantage of fabricating the device with CMOS is that it will allow manufacturers to sell it at a competitive price if it is commercialized. However, the first run was still rather expensive. The tiny transmitter he demonstrated cost US $100,000 to build.

Fujishima’s group hopes their transmitter can be used in satellite communications, or to set up a wireless link between cellular base stations. “I think that is a very promising application because space cannot be linked by fiber optics,” he says.

Elsewhere, companies and researchers have developed extra-sensitive receivers to reliably detect terahertz waves, which are quickly absorbed as they travel through the atmosphere.

Thomas Küerner, who has worked at TU Braunschweig in Germany on projects in which terahertz transmitters have been developed, calls the new research “quite a milestone.” Alongside Iwao Hosako, who is a coauthor with Fujishima, Küerner is leading the IEEE 802.15 Task Group 3d; the group’s mission is to develop a standard for devices that will operate in the 300-GHz band.

Küerner says the task group is considering four primary applications for 300-GHz devices. One is as a replacement for the wires inside devices with high-speed terahertz links that can send data from one part of the device to another. The second is using terahertz waves to enable the creation of wireless kiosks in retail stores that will let customers instantly download films to their devices instead of having to take a DVD home with them. The third, says Küerner, is to create wireless connections for data centers that can replace fiber optic cables. And the final application is to use terahertz waves for fronthaul or backhaul in cellular networks.

No comments:

Post a Comment